Wall Street Journal July 28 2011 »

What really happens to your cherished suits, shirts or dresses when you drop them off at the dry cleaners? Ray Smith discusses the new techniques that dry cleaners are trying as new rules prohibit a common cleaner.

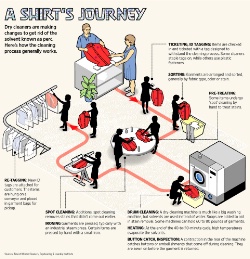

You drop your most cherished clothes at the dry cleaner, and they’re ticketed, thrown into a massive pile of garments and whisked away. To most consumers, what takes place behind the counter, where imposing machines rumble and steam hisses, is a mystery. What exactly goes on back there? Other common questions: Why do women’s shirts often cost more to clean than men’s, and why do only some stains come out? Adding to the confusion is a transition that is already shaking up the dry-cleaning industry. Many dry cleaners will be required to find new solvents to replace a widely used cleaning agent called perchloroethylene, or perc, by 2020. As a result, businesses are using a growing array of new methods to clean garments. Procter & Gamble Co. recently launched Tide Dry Cleaners, a chain of stores that use an alternative product, based on silicone and called GreenEarth. The result, for many people, is uncertainty. “I find myself looking at tags more to see if I can wash it,” says Alli Webb, the West Hollywood, Calif., co-founder of Drybar, a chain of blowout hair salons. She says she is nervous about chemicals and sometimes will drive farther to a cleaner that promotes itself as eco-friendly.

The shakeup is coming to an industry that has changed little for decades. While the Frenchman credited with inventing dry cleaning started with turpentine, perc has been used since the 1930s to clean clothes, and about 80% of cleaners still rely on it. Like turpentine—and benzene, kerosene and gasoline, which were also tried in the early years—perc is good at dissolving oil-based stains. It is pumped into a supersized washing machine to flush dirt from the clothes.

Stubborn stains from difficult-to-remove substances, such as ink, wine and mustard, are attacked by hand with chemicals that target particular substances. Bruce Barish, owner of New York City’s Ernest Winzer Cleaners, cites balsamic vinaigrette as “very hard to get out.” It’s a mix of both water-based and oily stains with a dark dye that is hard to remove—especially since most customers accidentally rub it in. The quality and service vary, in part because most dry cleaners are independently owned. There are 24,124 dry-cleaning and non-coin-operated laundry establishments in the U.S., according to the Census Bureau. But certain things hold true across the industry. In a 2009 study that examined 50 randomly selected dry cleaners, New York-based Floyd Advisory LLC found that women paid an average of 73% more than men for laundered shirts. Dry cleaners surveyed say women’s shirts don’t fit in their industrial presses as well as men’s and must be ironed by hand. Last year, market-research firm Mintel International found that 75% of women who had gone clothes-shopping in the past 12 months said they avoided buying clothes that required dry cleaning.

Indeed, it is customers’ low opinion of dry cleaning, in part, that sparked P&G’s new venture, the company says. P&G research found that a large percentage of consumers were generally dissatisfied with their dry cleaning, says Ross H. Holthouse, a spokesman for the consumer-product maker’s FutureWorks division. “They felt the stores were dark and that they walked into a black box and didn’t know what was happening,” he says. Tide Dry Cleaners stores, which use the branding of Tide laundry detergent, have valets that carry clothes to and from customers’ cars, lockers with customized passwords where consumers can drop off or pick up clothes after hours, and bar codes that keep track of customers’ data, including preferences. The company made sure the stores were bright and open, with the machines visible, Mr. Holthouse says. After starting with three test stores in Kansas City, Kan., the company opened the first Tide Dry Cleaner in Mason, Ohio, last fall, and two more Ohio stores opened in July. The company says it could have several hundred locations in a couple of years. P&G is also one of a growing number of businesses to use a cleaning substance other than perc. It uses P&G products such as Tide as well as perc alternative GreenEarth. Judge a Dry Cleaner Before Handing Over Clothing. Does it have a certificate or decal? The National Cleaners Association, Drycleaning Laundry Institute and America’s Best Cleaners all have qualifications a dry cleaner must meet to receive a certificate, such as passing tests in cleaning, stain removal and technical knowledge. Is it orderly? ‘If it’s clean and well run, chances are they are doing a better job with your clothes than some place that has stuff laying around,’ says Jack Gillis, director of public affairs for the Consumer Federation of America. Is the cleaning actually done there? Use an establishment with dry cleaning on the premises. “That will reduce the chances of something being lost” says Mr. Gillis. You can tell if the cleaning is done on site if there is equipment visible, or just ask if they send the clothes out to a separate facility. After you’ve chosen a cleaner and had your clothes cleaned, inspect the garments immediately when you pick them up, right there in the store. ‘A lot of us just grab it and go,’ Mr. Gillis says. Make sure your garments have been cleaned properly and pressed, and check for damages or for any lost items.

The Environmental Protection Agency has classified perc as a toxic air pollutant and potential human carcinogen. While the EPA mandated that cleaning businesses located in residential buildings phase out perc by the end of 2020, some states, including California, Illinois and New Jersey, have sought to end its use sooner and more broadly. As a result, alternative solvents have come on the market, claiming to clean just as well but with less harm to humans and the environment. Among the most popular are hydrocarbon, GreenEarth and a water-and-detergent method known as wet cleaning. The EPA hasn’t issued policy rulings on these substances, and dry cleaners aren’t required to say what they use. Some in the industry say the environmental concerns over perc have been overblown. Alan Spielvogel, director of technical services at the National Cleaners Association, a trade group, says the industry has taken steps over the years to reduce perc pollution, primarily by installing advanced machines. What’s more, he’s not convinced that the alternatives clean as well. About 60 dry cleaners in the U.S. use SystemK4, a new dry-cleaning solution made by Kreussler Inc. Alex Shvartshteyn, owner of London Cleaners in Cleveland, switched from GreenEarth to SystemK4 earlier this year and prefers the latter.

Kreussler wouldn’t disclose the chemical makeup of SystemK4, but it says the product leaves clothes softer and fresher-smelling than perc. “It won’t beat up the clothes as much as perc,” says Richard Fitzpatrick, vice president at Kreussler. But Mr. Spielvogel and others fear switching to alternatives will be costly. In many cases, dry cleaners will have to buy new machines, which can cost $45,000 to $100,000 or more. Converting to alternatives could increase the average dry-cleaning bill as owners pass on the costs of investing in new machines to customers. Increasing prices “is certainly an option” says Mary Scalco, acting chief executive officer of the Drycleaning and Laundry Institute, a trade association. “Most of the dry-cleaning industry is comprised of small mom and pop businesses.” When trying to decide what merits dry cleaning, consumers should start with the label. While some “dry clean only” items can be carefully washed at home, says Jack Gillis, director of public affairs at the Consumer Federation of America, “you’d be taking a risk if, like most of us, you didn’t know how the fabric would react to soap and water.” Some fibers and fabrics, such as viscose rayon, require waterless cleaning because they have “low wet strength,” while others such as wool might shrink, says Kay Obendorf, a professor of fiber science at Cornell University. In addition, some delicate materials, linings, finishings or trims won’t withstand the wash. Nadene Sabghir, of Coral Springs, Fla., says one of her daughter’s party dresses came back from the dry cleaners with melted sequins. Now, she doesn’t bring anything with “embellishment, sequins or something I really love” to the cleaners. “If I can hand-wash it or delicate-wash it, I will.”

Write to Ray A. Smith at ray.smith@wsj.com